Clemente Ciarrocca on the new art space he runs in Berlin-Kreuzberg, the formalities surrounding art practice, and the importance of shared wealth over value.

“There’s a lightness to good curating which is about making space before and beyond designing it.”

Kemmler Foundation: Clemente, you founded “Obelus” a little over a year ago. What motivated you?

Clemente Ciarrocca: The motivations and conditions behind Obelus were varied, but at the core was a sort of intuition, something like a blind-side feeling that we might be overlooking something important. I wanted to be a little nerdy and indulgent, be off focus and offer a space that was more directly critical, visionary, pathetic than what the book seems to command. And I was interested in thinking about form. I am very interested in these realities so integral to our shared experience of the world that we end up assuming them, so they take on a shaping, form-ing quality – think of how birth, death, language form in this sense a certain constancy among the infinite parameters of life. Reasoning along this line, it strikes me that as artists, we all tend to submit to one common procedure: we’re making something, we label it as 'done', and then expose it within mostly sanitized and hierarchical settings, which – absurdly – are actually designed and run with the goal of minimizing the type of raw, risky contact that got us to make the work in the very first place! Personally I feel this form, the 'how' of this common making, tends to engender distance. We remain what is withheld by this protocol. Could it be done some other way? So, Obelus is very much this - space to think not necessarily away from but around the assumptions that surround and eventually give shape to artistic practice – around the regime of sight, i.e. of what something looks like as opposed to how something looks, within the art experience, for instance – around the customs of art as asset, or the supremacy of value preservation and accretion – and this not to refuse but to diversify these assumptions. Once we realize all subjective narratives are intrinsically stiff, that a change in style without change in structure doesn’t yield liberation because the power behind it remains intact, formal diversity begins to open as a path of inquiry, and a new perspective I believe we could really benefit a lot from, were we to give it serious space in the industry while keeping inventive about how it could all be sustainable.

How do you feel these concerns sit within the city Berlin has become by the end of this century's first quarter?

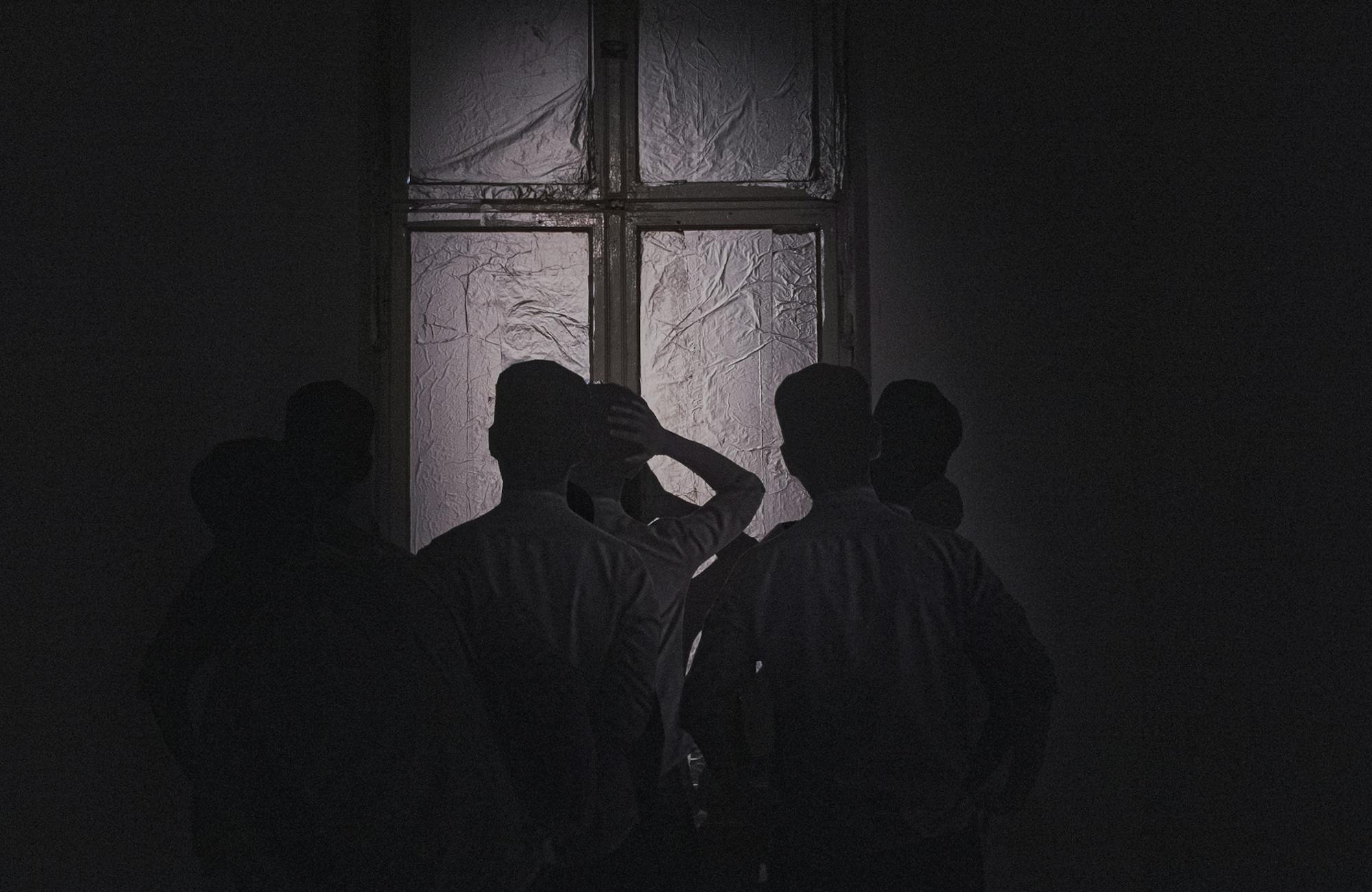

When the project officially took form I had been in Berlin for just over a year, which is about the time it took me to really begin to settle mentally and emotionally here – so I have only witnessed a very short and late part of this becoming. In my experience, this city is unique for how it can be as light as it can be heavy, letting you fly and rot with equal disregard, its past so deeply layered in the social everyday fabric it easily becomes at once invisible and present. I moved here from Los Angeles shortly before October 7th so my experience of Berlin has also been marked by rising police violence and censoring. As I kept tapping in and out of fully saturated scenes I began to realize I had followed a chimera or a myth in moving to this city, and felt both inhibited and lured by the aesthetics and dynamics of an art world run like any other product-based industry, although with no concrete bottom benchmark and so essentially operating like a dating platform (a car has to drive, a perfume smell, a piece of clothing be worn –but an artwork only needs to be desired and called so by the right people). I was reading Dionne Brand's "The Blue Clerk" which was making me reflect a lot around notions of withholding and visibility, and I had space, technically derelict and precarious but actually a really beautiful and pretty large space, this rundown flat transitioning between ownerships in Görli which I was using as a studio thanks to a friend that initially let me in. The generosity of this gesture made me realize I had this space also to share it with others, friends and artists who were interested in thinking around similar ideas, around withholding, around potentiality, and the spatial and temporal formalities of showing yourself to others.

How did this project emerge from your own prior artistic and curatorial experiences?

I am primarily an artist, and perhaps because it took its very first steps in the performative spaces of experimental theatre and film, my practice has always been explicitly multimaterial, spilling out of any one place or word I'd try to fit it in. From the very start it was pretty far-removed from being product- or even object-based, and it took me a while to even start thinking of using frames, which I began to do when I realized I could use framing as a way of creating pressure and holding things together that wouldn't otherwise hold. I've always seen my practice as one of assemblage, and my work as an edge or handle for a breathing, living thing, something like banks holding a river flow, a flow which would be the informal touches, the gatherings, the inspiration people draw from encountering the work and encountering each other through it or in its presence. I guess curating can be seen as a natural development of this spatial approach. The curatorial gesture is today perhaps harder than ever to pin down, which enables it with a mystery and a potential that fascinates me. At the end of day, each and every artist (and obviously every other practitioner) is, in a pretty literal sense, already curating their practice. Which might be a banal finding but it’s also a fact, and after all whether you call yourself an artist or a curator is more often than not essentially only an indictment of personality, or sometimes, of desire. I feel there's confusion today around what curators actually do or can or should do – is it about opening the conversation, is it about researched knowledge and selection ability, about the incredible capacity to control nausea at the 24th hour of non-stop networking, about vision, or all of these cooked up together? There’s no real need to define it, but for one thing I definitely believe there's a lightness to good curating which is about making space before and beyond designing it, about having the work unfold before drawing it in connections and binding it in ties knotted in big words and names.

In a passage on Obelus you write of the eponymous typographical mark that by questioning corrupt manuscript passages, whatever followed the obelus was “ a comment on the actual matter, meant to skim through the noise” – what is the noise that Obelus as an art space is trying to shut out?

Something that was on my mind with this idea of skimming, of moving across transversally, is the by now chewed and re-chewed awareness of how what we call contemporary art has basically become totally insular and virtually blind to dynamics that actually curb impact, which as a consequence, is a word that has become a bit taboo in our context. Who really believes contemporary art can be impactful any longer? And while these industry-wide dynamics are off scale for virtually any single one of its agents, I feel that one big issue here is also, partially in our control. I am thinking about how as artists we might be automatically – yet still consciously – buying into settings that are, again and again at each new iteration and concession, actively doing the numbing job. The four white walls, the mortuary-like documentation, the 'archival print', the opening, the tertiary citation of Deleuze's ideas on cinema in the press release... these are social technologies designed to gatekeep, enhance value, and please the collectors' eyes. They ultimately serve no other purpose. And that's fine, totally fine (and there is a lot happening under the hood—good gallerists create a lot more than just sales); but practice, which is how I refer to the ensemble of methods, objects, languages, and lives actually breathing under the term ‘art’, practice carries so much potential in excess of that. So this is also what Obelus is for: making space to slowly, gradually continue to see how practice can be hosted and transform if it starts to take some types of assumptions less seriously without necessarily being itself less rigorous.

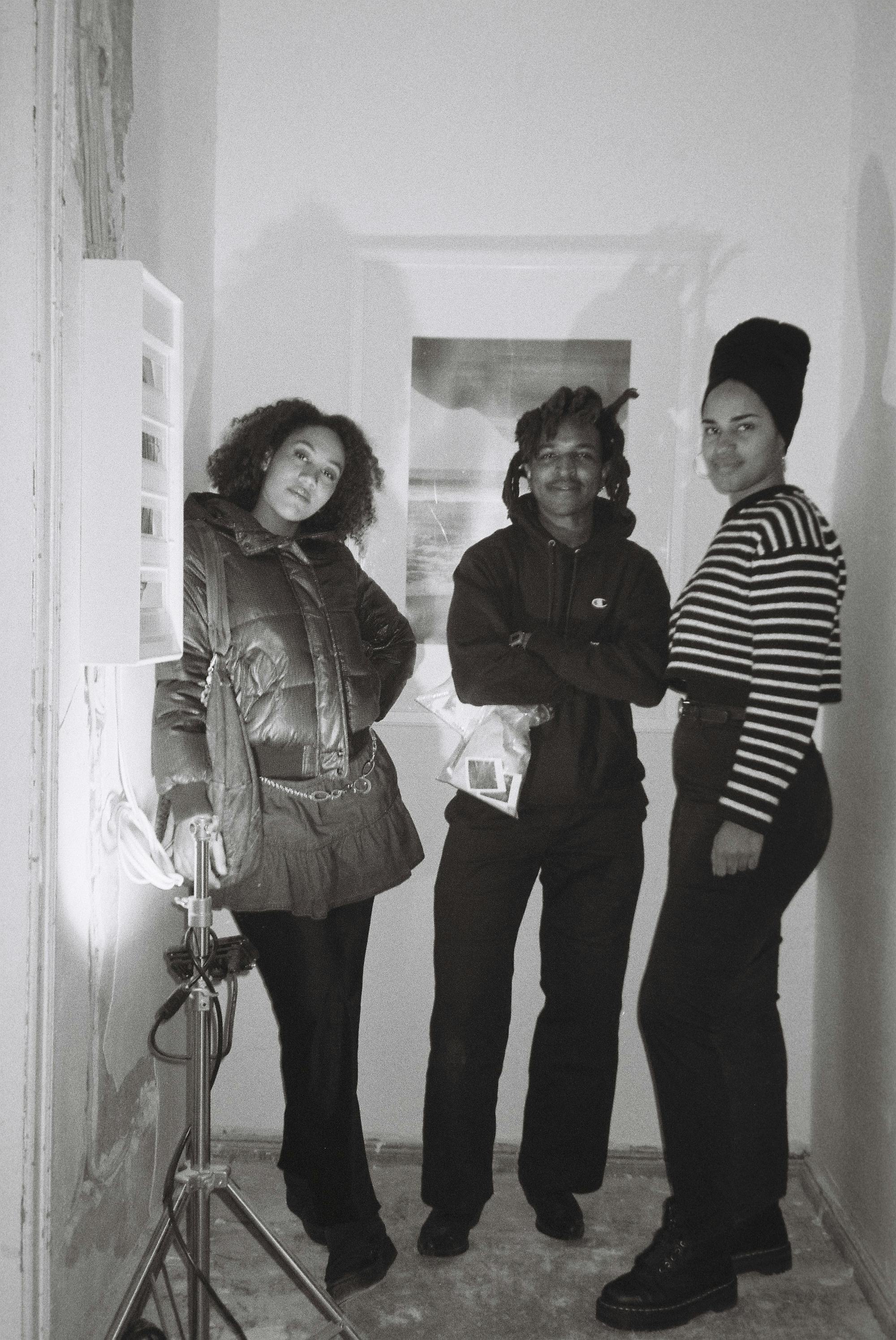

It’s interesting in this respect that Obelus has seen a wide range of different events already – from solo and duo shows to readings and seminars to film screenings. Where do you see throughlines connecting this diversity of formats?

Format-wise there's really no throughline but diversity itself. I mean that actually these formats are just categories and that, in the reality of each play-out, each format already includes the other. It's all one thing: gathering. A solo show is actually always a group show of multiple characters and personalities coming into the work; a duo show becomes a seminar during every tour the artists give of their install; as we replay in our minds all the movie scenes that compose our notions of romance, freedom, truth, guilt, etc, every seminar becomes a film screening; and so on. However there is definitely a more explicit throughline when it comes to intention, and that has been to pinch at some of the formal barriers that might be gatekeeping art from being impactful beyond its current paradigms of exposure. This is also why diversity is a fundamental element of the recipe here – the pinch happens naturally in and through diversification.

In fact, so far the most vivid throughline within Obelus has been operational: since its start the program has been developing mostly spontaneously and on short notice, and definitely by maintaining an economy of means. Obelus' economy is essentially contributional and geared toward creating value not through speculation but through community-building. We're non-commercial, which just means we don't conduct sales or operate on any service-based form of revenue, but the exhibited work is actually on sale, and all sale revenue goes to the artist. Across the past 12 months we've run a total of eight between weeks-long shows and one-day events by operating on about 3% of the average annual budget of a mid-tier European gallery. Obviously the art world's spending is completely off-point, with way too little of its excess going to its staff. Actually, something I'd love to include in our future programming is an Economics-oriented seminar, maybe focused on exploring perspectives on art as a luxury good and looking at the B2C dynamics in its adjacent markets, in order to produce a landscape of alternative ways artists may have to directly reach non-technical audiences. Because I think this is actually a huge issue –contemporary art's insularity, which is nothing new perhaps but it has grown really critical lately and inversely to the total decline of craftsmanship and artisanal work in the West. If we’re to believe Kathryn Bigelow, Andy Warhol said once (already decades ago) that the only art left in the West was cinema, and the way I read this is that cinema (and TV series today) actually enters homes and lives. Art instead remains in galleries, studio storages, multi-million mansions, and Swiss free-ports. Perhaps even more importantly than learning how not to be exploited by the market, which might after all even be delusional as a goal, artists must begin to learn themselves how to exploit it.

How do you mean?

I mean I believe that artists must have an understanding of how shared wealth, as opposed to value, can be generated from their practice. We basically have to be sort of economists, which actually is a term I’m borrowing from Félix González-Torres, even though I believe he meant it more in a sense of having a good grip on the social-economic historical conditions of the now in order to properly address it, which was imperative to him. Anyway, to get a sense of how core exploitative dynamics are to the art industry, just look at how both integral and 'strange' the relation between art education and art market is, for instance. Part of my training as an artist happened in an American school that is famously a bit utopian yet charges insanely high tuition rates with no real transparency on how the money is eventually spent within the school. When in a one-to-one meeting I asked the dean why there was no actual course on how to deal with post-graduation times and entry in the contemporary art industry, so that students could actually be offered both hard and soft tools not only to give an informed try at living off their work but also to get out of the very debt they likely incurred in to attend the school, the dean frowned, said he wasn't sure why, and that it seemed to him that the school was "in a relationship of anxiety with the art world." It makes no sense and too much sense at once.

What can you tell us about the upcoming Sam Cottington solo show at Obelus?

That we've been really figuring it out both slowly and all at once, somehow. As I am saying this I realize it kind of sounds paradoxical but it's exactly how it's feeling. We've been in conversation for a few months now and it's just starting to take shape, taking very interesting directions. Mediatically the show is bringing together and blurring structure and sculpture, which I'm very excited about. Part of what Sam is working from is the experience of threading for stability in a practical sense but also semantically, eventually reverting to a set of simple gestures or even commands that come to feel stable at the cost of erasure, repression, removal, all of which are somehow already grieved in the work. It’s kind of all nodding to a decorum while middle-fingering it, shaping an ambiguity which I personally find strong. And Sam's practice plays out its own paradox on the edge of the absurd: it’s a bit dada, somewhat minimal but in a picaresque sense, distilled, like a liquor is minimal. Jacques Tati's cinema is probably also somehow in there? What I can say is that we'll have a show that will definitely reward the curious—and unfold through the very ancient art of gossip...

At Kemmler Foundation, we often ask the artists and curators we collaborate with for contributions to our Utopian library project. What book(s) would you like to see in a library of utopias?

I really like this question. ‘Utopian’ brings me to future and discovery through the capacity to feel and think beyond the constraints of the current social norms. Utopia could be fictional but I don’t think it necessarily has to be speculative or unreal, so I think in a library of utopias I would also like to see books that charter the future actually by unveiling our own reality. I would include the whole of Sappho's poetry, Frank B. Wilderson III’s "Afropessimism", Hana Yanagihara’s "A Little Life", and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s "Teorema".

Programming at Obelus in 2025 has been supported by Kemmler Foundation.