The artist and film maker on her new film that was shown for the first time this spring at the Malta Biennale.

Kemmler Foundation: Franziska, the film Baħar Biss (Just Sea) that you presented this spring at the Malta Biennale comes from a very personal experience.

Franziska von Stenglin: In the fall of 2020 my father died after being ill for a long time. I again returned to Malta where my parents had lived for 3 years, to spend 2 weeks by myself. I needed some time alone. Grieving seemed more manageable under the late autumn Mediterranean sun than in cold grey Berlin.

During this whole time there I felt beside myself. My mind was hovering somewhere outside my body and the only way I could ground myself was to go on long runs. I like to run in nature, without headphones or a phone. Running with only the ocean, birds, the wind in my ear and the continuous sounds of my footsteps on the ground is meditation for me. So every day I drove my shitty mini rental car up to the cliffs of Dingli and started running. After a few kilometers I managed to shut off my brain, and my mind and body started merging back into each other.

"What started with the loss of my father turned into a film about a different loss."

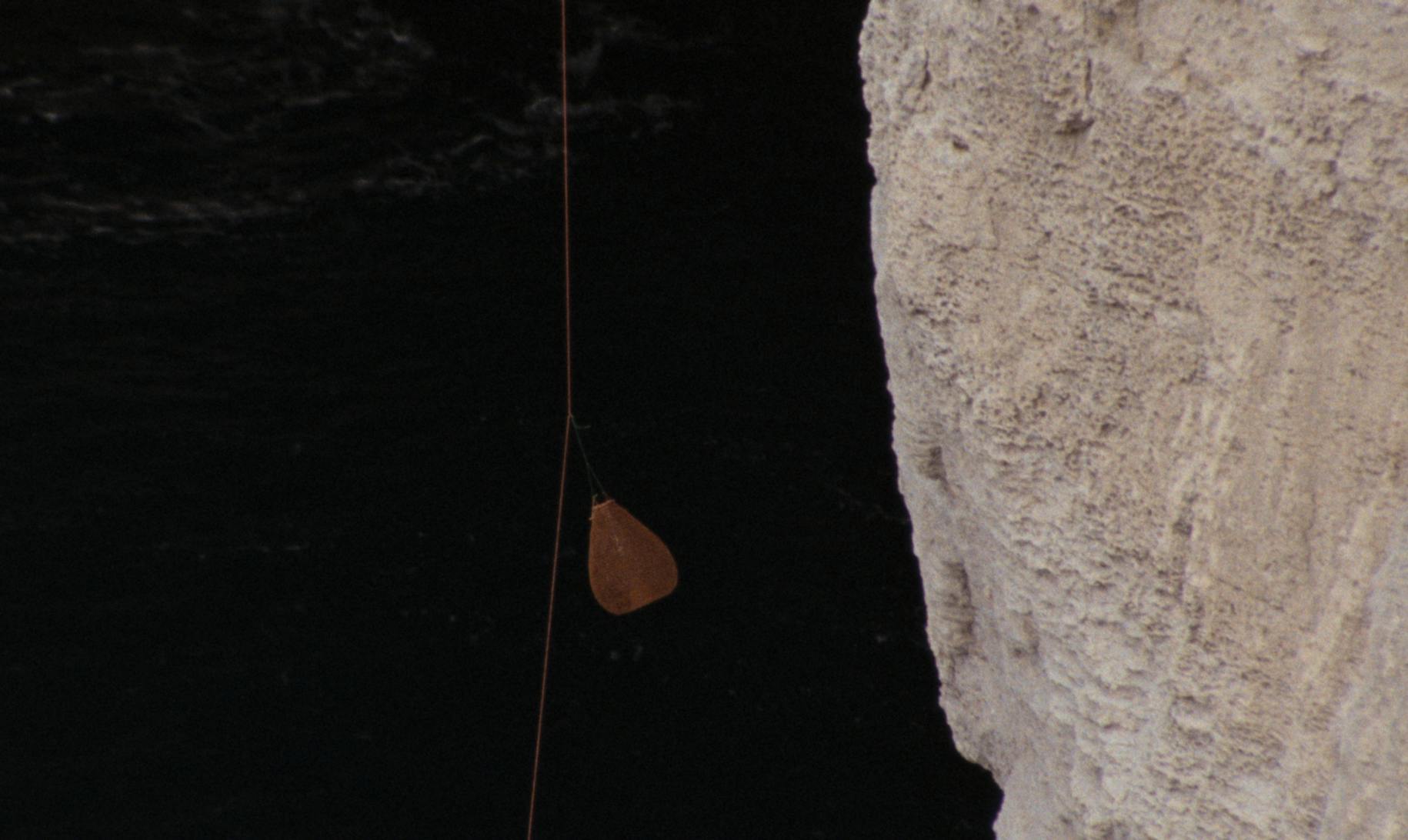

In those days in early November it was still quite warm. The wind was still and the sun was already hanging low on the horizon. From my car I descended to a path on the edge of the cliff running along, continuously aware of the 50 Meter drop to my left. The path wound itself along the cliff with a spectacular view over the still, glowing sea. I did not come across anyone until I saw a man sitting dangerously close to the edge. He was smoking and just staring out onto the water. When I came closer, I saw a line next to him attached to a rock that disappeared over the edge into the sea. I passed him and continued running. I had to climb down a ledge and jump across a small creek, when I saw another man again sitting suicidally close to the edge. This time there was a beautiful object lying next to him. He concentrated on calmly peeling out small fish from its interior, one by one. It was a fishing trap, but I had never before seen such a construction, a beautiful cylinder weaved out of thin cane. I continued to run, the landscape changed. The few, small bushes disappeared, I was now running on smooth sandstone-colored rock. The final stretch of the path took me back up the hill with a rope that I had to pull myself up onto a ledge followed by a steep ascent back to where my car was parked. Sweaty, out of breath, but much calmer I started driving back home.

What happened next?

The following days I returned to this spot running the same path. The weather stayed calm, with the deep sun dipping everything in golden light. This time I stopped to chat to the fishermen. When I meet people whose language I do not speak, but who I am curious about, I often manage to form a connection without many words needing to be exchanged. They spoke a little English and it was enough to communicate about how much they had caught (very little) and to ask me where I was from and what I was doing running on the cliffs of Dingli. Something about their grounded, patient focus, the slow pace of fishing, their content stayed with me. So when Emma Mattei, one of the curators asked me to hand in a proposal for the first edition of the Malta Biennale in spring of 2024 I decided I wanted to do a film about loss. What started with the loss of my father turned into a film about a different loss - the loss of marine life in the sea and and the cultures that tie us to it.

How did you experience filming on Malta?

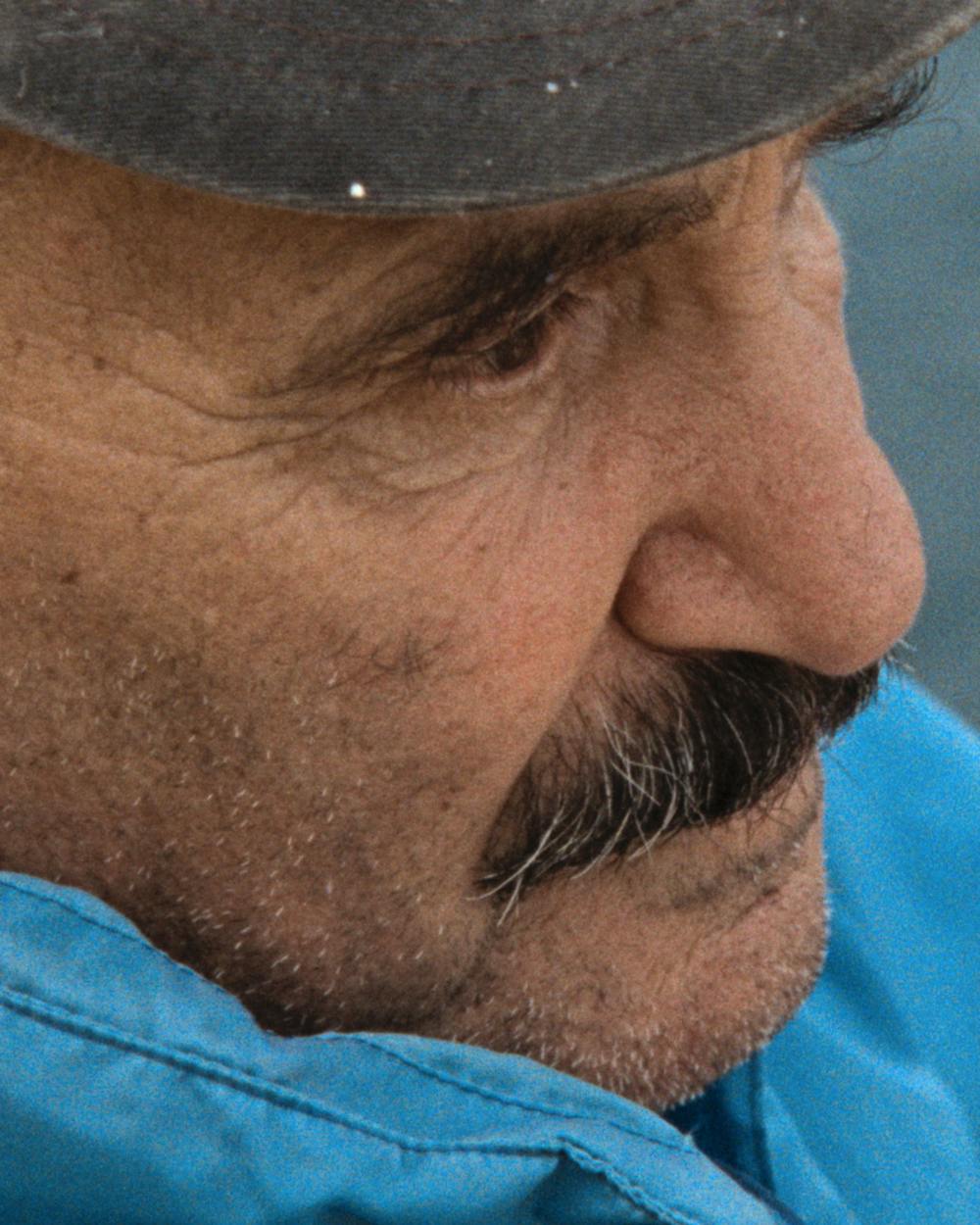

I only had two and a half weeks to organize everything. Luckily I know Malta quite well. Once Emma Mattei and I found Saviour Xuereb, the Protagonist in Gozo, I was less worried. An important part of making work for me are the connections I form during the process of making it. The only thing that was difficult was the weather. The wind at the end of December is not at all like in the beginning of November. But on the morning of the day we shot, the cliff it was calm. Carlos, my director of photography, and I were walking from where we had to leave the car behind, struggling to carry the equipment. After 200 meters I could see the meeting point which I had agreed on with Saviour. At 9 am, like clockwork, he appeared on the top of the ledge walking down towards us. It was magic. From then on I knew everything would be okay. On that day of shooting on the cliff I had the same calm feeling as I did when I was running 3 years earlier.

Saviour with his poetic eloquence and humor is a potent witness and narrator of what's happening.

Baħar Biss interweaves a personal and highly local experience with the global catastrophes of climate change and overfishing. How do these global changes affect the lives of the fishermen?

Overfishing and its catastrophic effects are not a new topics, but they are becoming more and more urgent. Saviour with his poetic eloquence and humor is a potent witness and narrator of what's happening. Hearing Saviour, who is so connected to the landscape, talking about his memories and observations – to me, that is very different from reading some abstract report on the consequences of climate change. He recounts memories of how the sea used to be and what it is now. Just like all the others who are older and have fished all their lives in the Maltese Islands, he sees what is happening every day. Of course this is changing the way they live, what they eat, how they are able to sustain themselves. But Saviour is not just a victim, he is also a perpetrator, like we all are. This was important for him to express in the film.

Unfortunately we missed the screening during the Malta biennale. Can you tell us about the public reaction and the atmosphere during the screening?

I wanted to shoot the film in Gozo, the neighbouring Island of Malta because I knew it was going to be shown there in the citadel. It was installed in the old 18th century kitchen. I really loved the food connection. The kitchen looked like a sculpture itself carved out of the same limestone rock, the same rock from the cliffs. It was an intimate situation that worked very well for the film. A lot of people reacted quite emotionally to the film. Saviour watched it twice in a row together with my mom and his wife Grace at the opening. He loved it. Many people who know Malta and told me the film is special to them. This means everything to me. Because I know that my love for my father, the grief, the love for this place and my friendship with Saviour is felt in Baħar Biss.

We also had a small team premiere in the back room of Saviour's brother's convenience shop, which doubles as a bar for him and his friends. We rented a screen and some speakers. Nenu made Gozitan pizza and snacks, Saviour's family and friends and also some of my friends came. We drank beers, Kinnie Whiskey, chatted and watched the film, played music and Saviour's cousin finished the evening with an accordion session.

Filming of Baħar Biss was realized with support from Kemmler Foundation.